By Dominik Lukeš, University of Oxford, UK.

There is no end of research around the effectiveness of every aspect of learning from video. Should the videos be long or short, should there be a face, how should text and images appear together on screen? Those are the questions we want to know answers to. We know what happens in a lab when a student watches a video for 15 minutes and then answers some questions about it. We know everything about those 15 minutes and we pay a lot of attention to how to make them the most effective 15 minutes we can. But that makes it seem as if those 15 minutes were everything. As if all the learning was done in those 15 minutes, nothing more to see, time to move on.

But when it comes down to it, we are far too focused on the production side of video. Things like sound, video angles, script, structure and production value are foremost in our minds. But that ignores the actual experience of students when it comes to multimedia. We must remember that any one video is always going to be only a very small portion of the learning journey. Students will spend as much time finding and choosing the right video, deciding when and how to watch it, and often, whether to watch it at all.

Watching the video is a discrete event, but learning from it is a continuous process. This process contains reflection, consolidation but it also has a dimension that is pure logistics – finding and navigating the video, searching through it, taking notes, etc. All of these aspects take time and effort, and advice on production of educational videos almost completely ignores them.

Lessons from YouTube

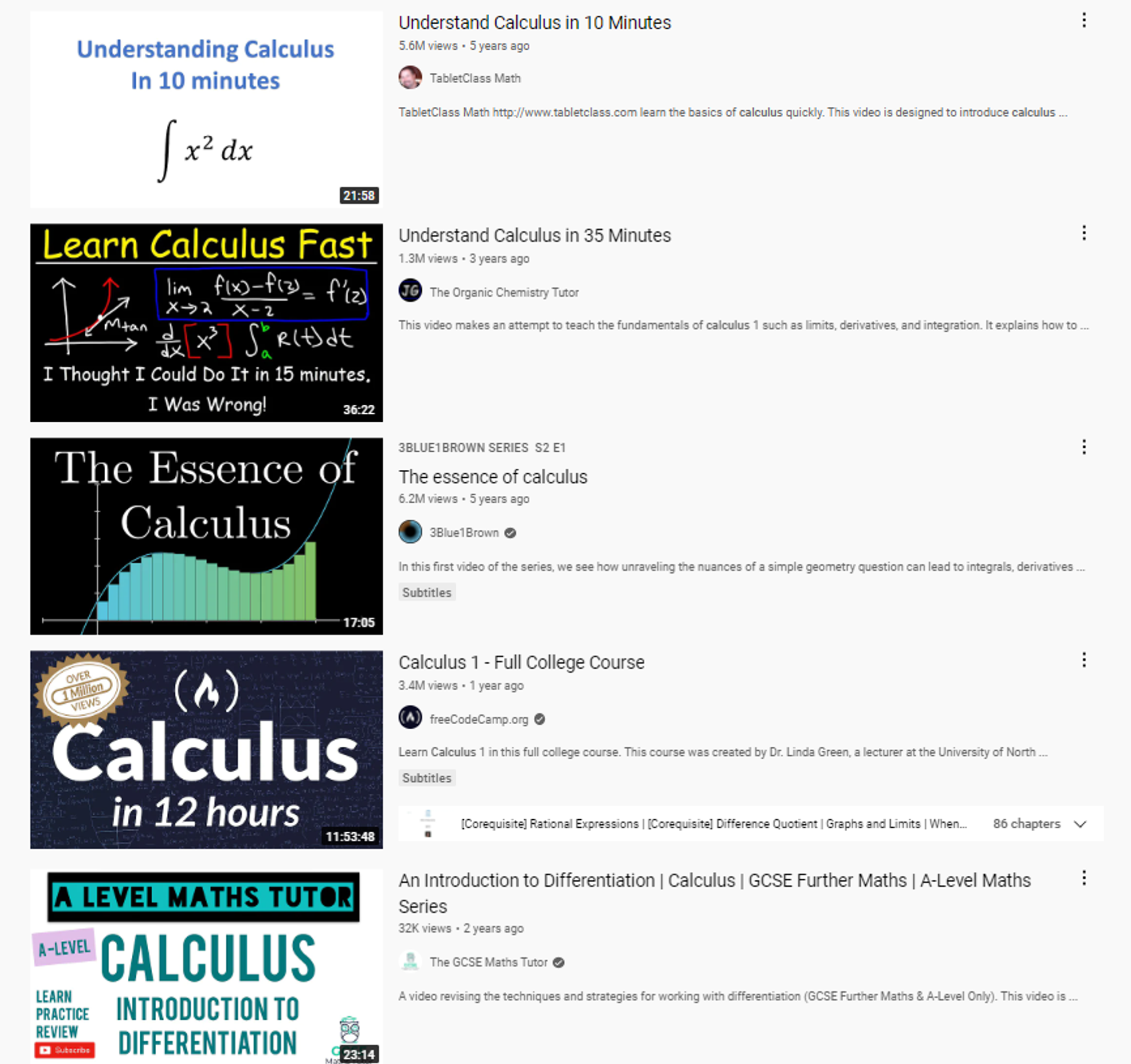

But we don’t have to go very far to find out what is important to viewers. The right lessons are waiting just a click away on YouTube, the place that started the modern revolution of video learning. To illustrate, let’s search for any academic topic. For instance, Calculus. All the main lessons can be found in the top 5 videos with combined views of 18 million. What can we learn from them? (Note: Everybody will get a slightly different list based on their location or viewing history but these lessons will be easy to find in any search.)

Production values and length

If we were interested in production, we may be surprised to find that every one of these videos is at least 3 times as long as the often promoted ideal length of a video of 6 minutes (one of them 120 times so). We will also see a remarkable lack of attention to “production value”. Only the third one by a famous professional YouTuber has animation and follows a script. The others are just someone talking over a digital whiteboard. Not far down the list, we will also find recordings of classroom lectures with millions of views.

Titles, thumbnails and viewers’ time

But even before we start investigating the production aspects, in fact, before we even click on a single video, we will notice three things. Each video has 1. a clear title, 2. a striking thumbnail which further elaborates the title, and 3. clear, to the point description, such that we can learn enough about the video from the truncated line. Because the search was quite generic, the titles are also short but long titles are no exception, as we can see from the fifth video.

What these three features do, is make it easy to find the video and decide whether it is relevant to our needs. How many students complain that they cannot find the video recordings of their lectures, or that they have a cryptic title and at best the date and at worst the file name. The idea that a video within a virtual learning environment could have an easily recognisable thumbnail is completely alien.

Yet, thumbnails are everything on YouTube. Popular channels often test different thumbnails to decide which one results in most engagement. Thumbnails don’t just replicate the title, they provide supporting information, often a hint of what is in the video, an enticing snapshot. The thumbnail is often an alternative title, the thing that causes people to click. Video is a visual medium, after all. It would be too much to expect educators to craft enticing thumbnails but video platforms could at least make it easier to choose the title slide, or better still do it automatically.

YouTube videos were driven to this because they compete for their viewers’ time and attention. But educators also compete for their students’ time, whether they know it or not. Students are busy with other studies and also their lives. They have jobs, they have friends, and, let’s face it, they have YouTube and TikTok. Educators know this intellectually but they are just not getting the same immediate feedback in terms of views as YouTube creators are.

Links and other useful things in the description

But YouTubers are considerate of their viewers’ time in other ways, as well. Who has not heard the magic words “link is in the description”. Most popular YouTube videos have extensive text in their description. It contains links to where the viewers can go next. Previous videos, collaborators’ channels, even affiliate products. They never rely on their viewers to “remember” a link or a number mentioned in the video. A popular thing to include in the description is a list of gear used to create the video; everyone wants to be a YouTuber after all. Sometimes, there will even be a summary of the argument, key points mentioned. Of our five videos, only the second one does that.

Time codes and video chapters

But perhaps the most important thing to be found in the description of more recent videos is linked time codes. These provide a sort of table of contents to the video. In the past, fans would provide linked time codes in the comments. But YouTube has now added new features to make timecodes easier and many creators provide links to parts of the videos themselves in the description. Their popularity is such that YouTube has started surfacing the navigation on the mobile app and is now piloting a feature to automatically create chapters.

Video chapters is a feature that lecture capture providers have long included in their platforms but educators often don’t know that it’s there or how to take advantage of it. All of our five videos are older, so only one of them contains links to time codes but a look around recent educational videos on YouTube shows their enormous popularity. Chapters are an essential tool for revision but they also provide a way to plan learning and offer a kind of summary of the main content.

What’s next and playlists

Navigation within a video is important. But the User Experience slogan: “your users spend most of their time on other websites” applies here, as well. For students watching a recording of a lecture, this is not their own learning activity. But even more importantly, they need to be able to easily switch between them, compare them, decide on just the right sequence.

YouTube creators use the description to provide links to related videos, next and previous videos in a sequence. Often they use a link on the screen using a built in function of YouTube. But even more importantly, they organise videos in playlists. Putting a series of recorded lectures into a playlist could help students much more than editing the videos.

Principles of multimedia learning and control

Richard Mayer’s Principles of Multimedia Learning are often used as the basis for recommendations about what effective educational videos look like. From this, it may seem as if they were not relevant here. But that is not the case. The principles of multimedia learning in fact very much emphasize the constructivist nature of learning. In particular, they stress the importance of learners building on existing knowledge and spending time developing new knowledge. This is best achieved when learners can control their input.

For example, in their 2018 paper on ‘What works and doesn’t work with instructional video’, Fiorella and Mayer choose ‘Segmenting’ as the first of the two most effective aspects of video.

“An important design issue concerns the extent to which learners should have control over the pace of a video lesson.”

Another relevant principle that is not mentioned as often is pre-training:

Provide pretraining in the names and characteristics of the key concepts in a lesson. **(Clark and Mayer, 2016, Elearning and the Science of Instruction)

Again, the text before, after the video, titles, thumbnails and chapters provide powerful cues about what to expect, thus enabling the student to plan and therefore better process the video.

Popular educational YouTubers seem to violate most of the multimedia principles quite freely, but they do want to give their viewers control. They think about the whole journey to the video, through the video, and from the video. And that is probably the most important lesson educators can learn from them.

Editor’s note: We are delighted to have Dominik as one of our speakers for the Media & Learning 2022 Conference on 2-3 June in Leuven, Belgium. He will be giving a talk entitled “Supporting teachers to support students? A case of two guides on educational video”

Author

Dominik Lukeš is an Assistive Technology Officer at the Centre for Teaching and Learning, University of Oxford, UK